In the heart of bustling bakeries and the quiet corners of home kitchens, flour is often taken for granted, a silent partner in the creation of beloved dishes. Yet, the journey from grain to flour is a fascinating odyssey that intertwines science, tradition, and craftsmanship. “From Grain to Flour: The Art of Cereal Milling Demystified” invites readers to explore the intricate process that transforms humble seeds into the fine powder that serves as the foundation for breads, pastries, and a myriad of culinary delights. As we peel back the layers of this ancient trade, we will uncover the meticulous techniques, innovations, and stories behind cereal milling—shedding light on the essential role it plays in our daily lives and in the very fabric of food culture. Join us in this exploration, and discover how the alchemy of milling not only shapes the ingredients we use but also connects us to the rich history of food production.

Understanding the Milling Process: A Journey Through Grains

The milling process is a fascinating journey that transforms raw grains into finely ground flour, a staple ingredient in kitchens around the world. At the heart of this process lies a combination of ancient techniques and modern technology. It begins with the careful selection of high-quality grains, such as wheat, corn, or rye. Each type of grain brings unique properties that influence the texture and flavor of the final product. Key steps in the milling process include:

- Cleaning: Removing impurities and debris from harvested grains.

- Conditioning: Adjusting moisture levels to prepare the grain for milling.

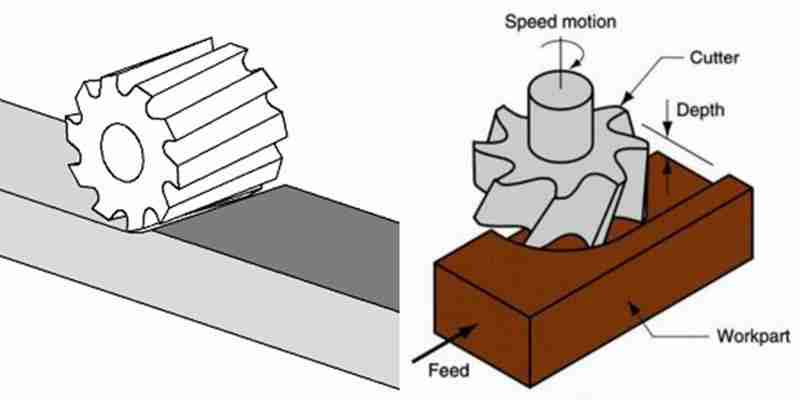

- Milling: Grinding the grain using various techniques, such as stone milling or roller milling.

- Sifting: Separating the flour into different grades based on particle size.

Understanding these steps reveals the artistry involved in milling, as the right combination of techniques and precision can yield flour that ranges from coarse to ultra-fine. For bakers, the type of flour used significantly affects the texture and rise of their baked goods. A table below highlights the primary types of flour produced from different grains and their common culinary uses:

| Type of Flour | Main Grain | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|

| All-Purpose Flour | Wheat | Breads, pastries, and sauces |

| Whole Wheat Flour | Wheat | Breads and health-focused recipes |

| Cornmeal | Corn | Polenta, cornbread, and tortillas |

| Rye Flour | Rye | Rye bread and crackers |

Types of Mills and Their Unique Functions in Flour Production

The world of flour production is as rich and diverse as the grains it transforms. Each type of mill serves a distinct purpose, elevating the humble grain into flour with unique textures and flavors. Roller mills are among the most common, employing a series of smoothly rotating cylinders to crush the grain, producing fine flour that’s ideal for baking. These mills provide precision, allowing millers to adjust the settings to achieve various grinds, from coarse to ultra-fine. Stone mills offer an age-old alternative, using natural stone to create a more artisanal product. The slower grinding process preserves essential oils and nutrients, ensuring a richer flavor and a heartier texture.

Additionally, hammer mills play a crucial role in producing coarser flours. They utilize high-speed rotating blades to pulverize the grain into smaller pieces, making them perfect for animal feed and specialty flours meant for unique recipes. For gluten-free flours, pin mills are especially valuable; they use high-speed impact to reduce grains, nuts, or seeds into fine powders without the risk of cross-contamination found in other milling methods. Each mill type embraces the grain with a different approach, reflecting the vast spectrum of flour used in countless culinary traditions around the globe.

Choosing the Right Grain: Factors Influencing Quality and Flavor

When it comes to producing high-quality flour, the selection of grain is paramount. Different varieties of grains possess unique characteristics that influence not only the texture and color of the flour but also its flavor profile. For instance, hard wheat is known for its high protein content, making it ideal for bread with a chewy texture, whereas soft wheat is favored for pastries and cakes due to its lower protein level. Some other key factors that determine the quality and flavor of grain include:

- Glycemic Index: Grains with a lower glycemic index offer a more balanced energy release.

- Terroir: The environment where the grain is cultivated affects its taste and nutrient composition.

- Harvest Timing: Grains harvested at the optimal time yield better flavor.

- Storage Conditions: Proper storage can prevent spoilage and preserve grain quality.

The variety of grain also plays a critical role in how it performs during milling and baking. Bakers often look for specific traits like moisture content and kernel hardness, which directly affect flour performance. For example, durum wheat, with its hard kernels, is used for pasta and semolina because it creates a firm structure that holds shape well during cooking. To illustrate some common grain types and their ideal uses, consider the following table:

| Grain Type | Common Uses | Flavor Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Hard Red Winter Wheat | Bread, rolls | Nutty, robust |

| Soft White Wheat | Cakes, pastries | Delicate, sweet |

| Durum Wheat | Pasta | Earthy, grainy |

| Barley | Soups, stews | Mild, slightly sweet |

The Future of Milling: Innovations and Sustainable Practices in Flour Production

As the demand for sustainably sourced ingredients rises, the milling industry is evolving to incorporate innovative technologies designed to reduce waste and enhance efficiency. These advancements not only improve the precision of flour production but also focus on minimizing environmental impact. Among the exciting developments are vertical milling systems, which use less energy and produce less noise than traditional methods. Additionally, smart sensors are being implemented to monitor grain quality and optimize grinding processes, resulting in higher yields and producing flour that ranks high in nutritional value.

Another pathway to sustainable flour production is through the utilization of alternative grains and by-products. Mills are exploring the milling of grains like quinoa, millet, and spelt, which offer unique flavors and nutritional profiles while ensuring a diversified supply chain. Moreover, the use of circular economy practices allows by-products from milling—like bran and germ—to be repurposed in the food industry, minimizing waste and creating new revenue streams. The integration of these practices not only supports farmers and local economies but also fosters an eco-friendly production cycle that benefits both consumers and the planet.

In Conclusion

the journey from grain to flour is a remarkable transformation that intertwines nature’s gifts with human ingenuity. By understanding the intricate processes of cereal milling, we not only appreciate the artistry involved but also the vital role it plays in our daily lives. Each grain carries with it stories of agriculture and tradition, while every bag of flour holds the potential for culinary exploration and innovation. As we embrace the simplicity of a basic ingredient, let us also celebrate the craftsmanship that brings it from the fields to our kitchens. So whether you’re baking a rustic loaf or whipping up a delicate pastry, remember that within each fine ground grain lies an invitation to create, nurture, and savor the rich heritage of flour.