From Grain to Flour: The Art of Maize Milling Explained

In the world of culinary traditions, few ingredients hold the same revered status as maize. From the vibrant fields where it grows to the bustling kitchens that transform it into cherished dishes, maize has woven itself into the fabric of countless cultures. Yet, the journey from grain to flour is not merely a series of mechanical steps; it is an art form steeped in history, precision, and innovation. This article delves into the intricate process of maize milling, exploring its historical significance, the techniques employed, and the delicate balance of tradition and technology that shapes the flour we use today. Join us as we uncover the secrets of this essential grain, revealing the craftsmanship behind its transformation into the versatile flour that nourishes our world.

Understanding the Maize Grain: Anatomy and Varieties

The maize grain, a staple in many cultures, is a marvel of botanical engineering. Its structure consists of three primary components: the pericarp, or outer shell, which protects the seed; the endosperm, a starchy core that serves as the grain’s energy reservoir; and the germ, the embryo from which new plants grow. Each part plays a critical role in the grain’s nutritional value and culinary versatility. Understanding these components is essential for optimizing milling processes, as different milling techniques can extract varying proportions of each component, impacting the flavor and texture of the flour produced.

When it comes to varieties, maize is incredibly diverse, with numerous cultivars available worldwide. They can be broadly categorized into dent corn, known for its high starch content; flint corn, which has a harder, glossy kernel; sweet corn, prized for its high sugar levels; and popcorn, characterized by its unique ability to expand when heated. Each type serves specific gastronomic purposes, influencing how they are processed during milling. Below is a concise table that showcases the distinctive characteristics of these various maize types:

| Type of Maize | Key Characteristics | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Dent Corn | High starch content, soft endosperm | Animal feed, industrial products |

| Flint Corn | Hard, glassy texture | Cornmeal, grinding flour |

| Sweet Corn | High sugar content, tender kernels | Fresh consumption, canned goods |

| Popcorn | Hard outer shell, moisture inside | Snacks, gourmet popcorn |

The Milling Process Unveiled: Techniques and Technologies

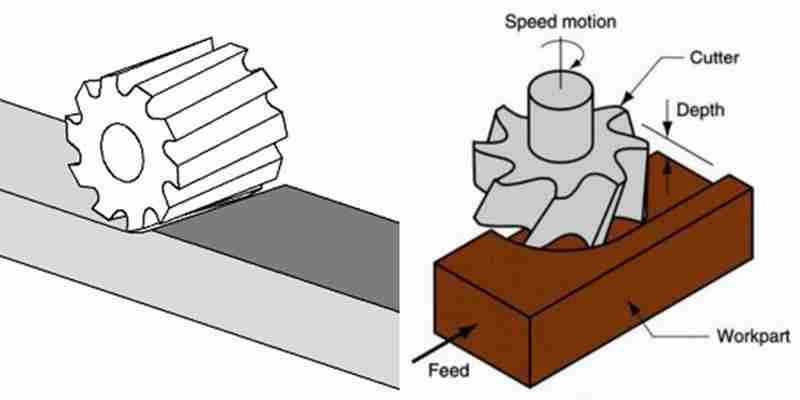

The journey from maize to flour is a fascinating interplay of ancient techniques and modern technologies, each playing a vital role in creating the final product. At the heart of this process lies the dry milling method, which utilizes machines such as roller mills and impact mills to break down grains into fine particles. The traditional stone milling, still beloved by some artisans, combines precision with a touch of nostalgia, grinding the grains between two stones to produce a coarse or fine flour while preserving the kernel’s natural oils and nutrients. In contrast, industrial milling employs sophisticated technology to maximize efficiency and yield, ensuring a consistent product for mass consumption.

The actual milling process can be broken down into several key phases, which include:

- Cleaning: Grains are thoroughly cleaned to remove impurities and foreign materials.

- Conditioning: Moisture is added to the grains, making them easier to mill by altering their texture.

- Milling: The conditioned grains are then ground using various techniques to produce flour of different textures.

- Sieving: The flour is sieved to separate different particle sizes, ensuring uniformity in the final product.

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Dry Milling | High efficiency, continuous production | Possible nutrient loss |

| Stone Milling | Retains flavor and nutrients | Slower process, higher labor intensity |

| Wet Milling | Higher extraction rates | More complex machinery, higher costs |

Quality Control in Flour Production: Ensuring Purity and Consistency

In the intricate journey from grain to flour, ensuring the purity and consistency of maize is paramount. Each batch of maize undergoes rigorous inspection before milling, emphasizing both visual and laboratory assessments. Visual checks involve examining the grain for any signs of pests, mold, or discoloration, while laboratory tests ensure moisture content and protein levels meet industry standards. This multi-faceted approach helps maintain the high quality that consumers expect, laying the foundation for an exceptional flour product.

Once the milling process commences, quality checkpoints are strategically placed throughout. During milling, the maize is monitored for particle size, ensuring that each grain is ground uniformly. Moreover, the flour is subjected to baking tests to evaluate its performance in end products. The quality control team analyzes the results, adjusting the milling parameters as necessary to achieve optimal consistency. This diligent attention to detail not only enhances the flour’s baking qualities but also cultivates trust in a product that is both reliable and safe for the consumer.

| Quality Factor | Measurement Method | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Inspection | Manual Assessment | Identifies defects and impurities |

| Moisture Content | Lab Testing | Affects shelf life and texture |

| Particle Size | Sifting Analysis | Influences baking performance |

| Baking Tests | Practical Application | Ensures end-user satisfaction |

Culinary Applications of Maize Flour: Tips for Home Cooks and Bakers

Maize flour serves as a versatile ingredient that can elevate a variety of dishes in your kitchen. With its distinct flavor and texture, it complements both sweet and savory recipes. Here are some tips for incorporating maize flour into your cooking and baking:

- Pancakes and Waffles: Substitute up to 50% of the wheat flour with maize flour for a unique flavor that will delight your breakfast.

- Bread and Baking: Use maize flour to create gluten-free bread or enhance the taste of traditional loaves with a touch of sweetness.

- Thickening Agent: Add maize flour to soups and stews for a lovely texture and richness while also increasing nutritional value.

- Corn Tortillas: Try making homemade corn tortillas by mixing maize flour with a little water and salt for an authentic taste.

Cooking with maize flour not only boosts flavor but also enriches your meals with essential nutrients. To help you get started, here’s a simple comparison table for standard uses of maize flour:

| Dish Type | Maize Flour Role | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Pancakes | Alternative Flour | Rich flavor, light texture |

| Soups | Thickening Agent | Adds nutrition and smoothness |

| Breads | Base Ingredient | Rich aroma, gluten-free options |

| Desserts | Substitute for Cake Flour | Unique sweetness and tenderness |

With these insights into culinary applications, home cooks and bakers can easily experiment and discover the full potential of maize flour in their everyday recipes.

Wrapping Up

the journey from grain to flour is not merely a process; it is an art form steeped in tradition and innovation. As we’ve explored, maize milling serves as a vital link between nature’s bounty and the bountiful dishes it inspires. From the careful selection of kernels to the precise grinding techniques, each step contributes to the unique character and flavor of the finished product. By understanding the intricacies of maize milling, we gain a deeper appreciation for this staple grain that has nourished countless cultures and communities throughout history. Whether you’re a chef in pursuit of the perfect texture or a home cook experimenting with new recipes, the world of maize flour holds endless possibilities. As we continue to celebrate and refine this ancient craft, we invite you to embrace the grain-to-flour journey in your own culinary endeavors, discovering the rich potential that lies within each kernel.